The following project is not listed on the NSF ETAP portal due to technical constraints: Bioinspired Wave Energy in the Real Ocean: From Data to Design (see last entry on this page for details). If you are interested in this project, please say so clearly in your writing prompts and we will be sure to list it as your first choice during the selection process!

Understanding eelgrass population dynamics through paleoecology

Dr. Sandy Wyllie-Echeverria, Friday Harbor Laboratories, University of Washington

Dr. Kendall Valentine, University of Washington

Dr. Bruce Finney, Idaho State University

Seagrasses are a critical part of coastal ecosystems, providing a unique habitat, but have been disappearing at a rapid rate globally. Seagrass distributions are controlled by a number of factors, including sediment characteristics. In this project, we aim to understand how changes in environmental factors control the persistence of the seagrass, Zostera marina, eelgrass, using a paleoecological approach. Our study site, False Bay, San Juan Island, is a shallow water bay that lies within the Salish Sea region of Washington State and is a marine reserve managed by the Friday Harbor Laboratories, University of Washington. We will reconstruct the environmental history of the bay from analysis of sediment cores spanning to the last ice age. Reconstruction of eelgrass abundance will be determined by downcore changes in carbon isotopes (δ13C), a proxy for its abundance. Corresponding sedimentary environments will be determined through grain-size, organic content and other analyses. The sediment and isotope data open a “window into the past” that will allow us to determine favorable conditions for eelgrass, and sequences of changes leading to eelgrass decline.

The Functional Role of Skin in Armored Fishes

Dr. Karly Cohen, UW Friday Harbor Labs

Dr. Cassandra Donatelli, UW Tacoma School of Engineering and Technology

Armor in fishes is incredibly diverse, ranging from bony plates to rigid overlapping scales to sandpaper-like denticles. Despite being covered in rigid structures, these fishes remain flexible and adaptable in complex environments. This suggests that armor alone does not explain how these systems function; the often overlooked skin and other soft connective tissues must also play an important role in skin and body mechanics.

Armor in fishes is incredibly diverse, ranging from bony plates to rigid overlapping scales to sandpaper-like denticles. Despite being covered in rigid structures, these fishes remain flexible and adaptable in complex environments. This suggests that armor alone does not explain how these systems function; the often overlooked skin and other soft connective tissues must also play an important role in skin and body mechanics.

This REU project will focus on how fish skin and connective tissue interact with armor during stretching and deformation. Rather than treating armor as a rigid shell, we will explore the idea that protection emerges from the combination of both skin and scales. In particular, we are interested in how stretching of the skin changes the overlap between neighboring armor plates, and whether these relationships differ across species.

The project will combine field collection, advanced imaging using Computed Tomography (CT) scanning and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), histology, and mechanical testing. The student will participate in collecting fishes at several sites around San Juan Island and will design, build and use a mechanical testing setup to stretch fresh skin samples. As the tissue is stretched, changes in deformation and armor plate overlap will be recorded using imaging and video analysis. These measurements will be used to describe the relationship between tissue strain and armor behavior in different species.

By focusing on soft tissue rather than armor plates alone, this work addresses a major gap in how biological armor systems are typically studied. Understanding how skin and other connective tissue contributes to flexibility, protection, and energy absorption has implications for functional morphology and biomechanics, as well as for bioinspired design strategies that seek to combine stiffness and flexibility in engineered materials. The student will gain hands-on experience with marine fieldwork, mechanical testing, image and video analysis, experimental design, and data visualization, while working in an interdisciplinary environment that bridges biology and engineering.

This project is well suited for students interested in biomechanics, morphology, or bioinspired design. No prior experience with fish or mechanical testing is required, only curiosity and a willingness to learn. As with all Friday Harbor Labs projects, students are encouraged to fully engage with the FHL community, take advantage of the unique field and lab setting, and immerse themselves in the collaborative research across campus.

Biotic and abiotic factors influencing kelp bed communities in the Salish Sea

Dr. Katie Dobkowski, Everett Community College and Friday Harbor Labs

Bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) is an annual kelp species that provides the bulk of the complex three-dimensional habitat space in rocky subtidal habitats of the San Juan Islands and elsewhere in Washington State. There are a variety of potential summer projects that focus on investigating biotic and abiotic factors influencing bull kelp across their complicated life history using a combination of lab and field work. Topics of interest include investigating:

- green sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis), red sea urchin (Mesocentrotus franciscanus), Northern kelp crab (Pugettia producta), and graceful kelp crab (P. gracilis) feeding preferences (in the lab at ambient and elevated temperatures) and distribution and abundance (in the field; intertidal, snorkel or SCUBA surveys)

- influence of competition from invasive wireweed (Sargassum muticum) on nearshore habitats and species, including bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana)

- effects of changing ocean conditions, such as temperature, on invertebrate feeding rates (urchins, kelp crabs)

Subtidal data collection using snorkeling methods is possible, but diving OR snorkeling is NOT a requirement for any of these projects, very successful field data collection can happen on the shore or from boats as well! A better understanding of the dynamics and interactions of N. luetkeana beds in the Salish Sea is crucial not only because they create valuable habitat for economically and ecologically important species, but also to inform management decisions and restoration efforts in a changing ocean.

Environmental DNA as a Tool to Assess the Biodiversity of Marine Fishes Along the Coast of San Juan Island

Dr. Joseph Heras, CSU San Bernardino

Environmental DNA (eDNA) offers a powerful, low-impact approach for detecting biodiversity and assessing changes in species presence along coastlines. Unlike traditional survey methods (e.g., visual transects and trapping), which can be constrained by tidal conditions and observer bias, eDNA enables the detection of species from trace genetic material present in saltwater. In this project, eDNA tools will be used to examine the biodiversity of marine fishes in the Salish Sea along the coastline of San Juan Island. Target families include Cottidae (sculpins), Embiotocidae (surfperches), Gobiidae (gobies), Stichaeidae (pricklebacks), Clupeidae (herrings), Opistognathidae (jawfishes), Liparidae (snailfishes), Pholidae (gunnels), and Gadidae (cods). Sampling sites will include both intertidal and subtidal habitats around the island. We will deploy 3D-printed spheres containing internal filters to passively capture eDNA from the surrounding water. Following collection, filters will be transported to Friday Harbor Laboratories, where DNA will be extracted and a short genetic marker sequenced to characterize fish community composition around the island. Throughout the program, the REU student will gain hands-on experience in field sampling, fish identification, DNA extractions, eDNA sequencing workflows, and bioinformatic and statistical analyses using tools such as R. Students will develop an understanding of how molecular techniques can be applied to questions in ecology, evolution, and conservation, while contributing novel data on nearshore fish communities of the Pacific Northwest. Prior experience in fieldwork, genetics, or bioinformatics is beneficial but not required; enthusiasm for marine ecology and molecular approaches is strongly encouraged.

Winners, losers and bystanders: male competition and female preferences in maritime earwigs

Dr. Vik Iyengar, Villanova University

My research involves the behavior of arthropods, a highly abundant group whose extraordinary evolutionary success can be partly attributed to the remarkable diversity of their mating systems. Sexual selection, defined as differences in reproductive success due to competition for mates, often manifests itself in morphological differences between sexes (i.e., sexually-dimorphic traits) as the result of intrasexual male battles for females, intersexual female choice based on male traits, or a combination of both. The maritime earwig (Anisolabis maritima) is an insect well-suited for such behavioral studies because males differ markedly from females in body size (males are more variable in size, and often larger, than females) and weaponry (males possess asymmetrical, curved forceps whereas females have straight forceps). Maritime earwigs are found in high densities under driftwood, and they interact frequently with each other in both contests for mates and food, often using their posterior pincers to aggressively attack each other to secure the resource. Males typically resolve their disputes non-lethally by squeezing each other’s abdomens, whereas females strike and often kill conspecifics while vigorously guarding their nests. Although our research group has described the outcomes of competition and choice in maritime earwigs, we have not explored the mechanisms by which males achieve success and female judge mate quality within the context of fighting. This summer we will continue lab and field investigations to determine whether the outcome of intrasexual competition is influenced by the male’s past fighting experience (winner/loser effects) and can alter a female’s mating preference (bystander effects).

Coastal Fog and Climate Refugia: Combining photos, temperature sensors, and tide tables with satellite remote sensing and physical models

Dr. Jessica Lundquist, Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Washington

Marine stratus and coastal fog are common along the western U.S. coast, but studies disagree about whether fog frequency is increasing or decreasing. The marine boundary layer is fast-moving, hard to forecast, a hazard for air and sea navigation, and provides huge contrasts in air temperatures during summer heat waves. Fog and humidity are critical to Washington area intertidal organisms due to the timing of the tides, where low tides disproportionately occur during the hottest times of the day. For this project, undergraduate interns will deploy and collect timelapse cameras along with air temperature and relative humidity sensors at coastal and interior sites across San Juan Island, adding data to measurements taken since summer 2021. Interns will analyze this data in the context of ocean temperatures, regional winds, tides, and heat waves to understand when and where small-scale temperature variations matter the most to local ecology. Interns will work with python programming tutorials to plot and evaluate forecasts from high resolution weather (WRF, https://a.atmos.washington.edu/wrfrt/info.html ) and ocean (LiveOcean, https://faculty.washington.edu/pmacc/LO/LiveOcean.html ) models, as well as a variety of satellite data, to put the local observations in a regional context and better understand the accuracy of different ways of representing temperatures along the coast. Prior programming experience is a plus but not required; anyone with an interest to learn is encouraged to apply.

Sea Star Vision, Eye Growth, and Behavior

Dr. Julia Notar, Friday Harbor Labs, University of Washington

It has been observed for over a century that sea stars have eyes, but until the last decade very little work has been done to understand their vision. A handful of sea star species have had the optical qualities of their eyes studied, and a few species have been tested to show that they have true image-forming vision. The sea star species of the Pacific Northwest remain unstudied in both of these areas. In addition, little is known generally about how sea star eyes change as the animal grows from a tiny, 5-armed juvenile a few millimeters in size to an adult that may, depending on species, grow to more than a meter across and have over 20 arms. Do juvenile stars have smaller eyes (which often means blurrier vision)? What behaviors do juveniles and adults use their vision for? How is eye growth different for species that continually add arms as they grow, like the endangered Pycnopodia helianthoides? (i.e. Does a new eye catch up in size to the original 5 eyes, or is it always smaller?)

This project seeks to understand the vision of a diversity of sea star species endemic to the Pacific Northwest at adult and juvenile life stages. Work will include characterizing the optical qualities of eyes (which requires fixing, staining, and imaging eye tissue) and running behavioral experiments to study the visual responses of adult and juvenile stars. Field collection of live animals may also be required. This project will give us a better understanding of the behavioral ecology of these important benthic predators. Students who are enthusiastic about understanding the lives of “weird” invertebrates like sea stars and are curious about the sensory worlds of animals are particularly encouraged to apply. No prior experience with specific research techniques is necessary, just a willingness to learn.

Documenting Phyllaplysia taylori exploration of eelgrass habitat structure under temperature and tidal regimes

This project will be supervised by Dr. Sandy Wyllie-Echeverria and conducted in collaboration with student researchers supervised by Dr. Richelle Tanner at a lab facility in Southern California.

The complex habitat structure of Zostera marina eelgrass provides essential ecosystem services to its residents, in both shelter and food. For grazers living within the ever-swaying leaves, this provides an opportunity to explore the water canopy without the ability to swim, providing potential areas for resting, grazing, and laying eggs. Phyllaplysia taylori, an epiphyte-grazing sea slug that exclusively lives on eelgrass, is anecdotally known to use the full eelgrass canopy for distinct life history periods and functions. However, this knowledge has not been empirically confirmed. Additionally, it is unclear whether P. taylori’s behaviors in the eelgrass canopy are linked to abiotic drivers like warmer temperatures and more dramatic tides. Previous work by a UW FHL REU student in 2020 explored the influence of lugworm behavior on eelgrass seed burial, demonstrating the importance of infaunal organisms to eelgrass ecosystems. Here, we seek to understand how above-ground eelgrass dynamics are impacted by other invertebrates. In this project, the undergraduate researcher will use a mesocosm-based study to experimentally manipulate tides and temperatures of eelgrass habitats hosting P. taylori and document the three-dimensional use of the eelgrass habitat by P. taylori in all life stages. This study will incorporate methods in community ecology, animal husbandry, microscopy, and statistical analyses. As Friday Harbor is positioned near the northernmost range edge, we will also be pairing this with a reciprocal experiment at the southernmost edge in San Pedro, CA with Chapman University undergraduate researchers to explore how habitat use by P. taylori is shaped by geographic range. Thus, there is the additional opportunity and expectation of learning how to manage cross-institutional collaborations and datasets.

When do the iron-clad teeth of chitons develop?

Dr. Rebecca Varney, University of Nebraska Lincoln

Key words: biomineralization, embryology, confocal microscopy, transcriptomics

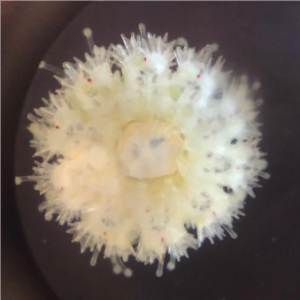

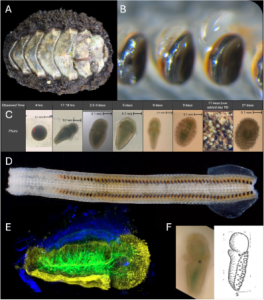

Chitons (Polyplacophora) are intertidal molluscs that grow iron teeth. Last summer, a previous REU student developed methods to spawn chitons at FHL, providing the first glimpse of how teeth emerge. However, we didn’t expect spawning to work, which meant that we were unprepared to image and document our larvae! This summer, I’m coming back prepared. Together, an REU student and I will: 1) collect and spawn chitons again; 2) work with Dr. Jim Truman (an FHL resident confocal wizard) to stain and image embryos the entire way through development; 3) work with Dr. Jon Allen to mark chitin at timepoints during development and determine how it moves in the embryo; 4) amplify transcriptomes from larvae at each key stage of development. We will also fix embryos for microscopy, and perform some SEM on site. You will learn to handle marine embryos with proper technique, use light microscopes, confocal microscopes, and SEM, generate RNA sequencing libraries from tiny samples, explore biomineralization as a general field, and hang out with the invertebrate zoology class (which I will be teaching concurrently). This project will be collaborative, so you will have the benefit of learning from several experts in the field. You’ll also be welcome to participate in the inverts class as much as you wish as you watch your “little green balls with eyes” grow into chitons.

Bioinspired Wave Energy in the Real Ocean: From Data to Design

Molly Grear – Pacific Northwest National Laboratories

Can the ocean power its own science and can understanding biology help make that power work better? This interdisciplinary summer research project at Friday Harbor Labs brings together engineering, oceanography, ecology, and biomechanics to explore small-scale wave energy systems in real coastal environments. Students will combine field deployment, data analysis, and bioinspired design, gaining experience across the full research pipeline while staying actively engaged throughout the summer.

Students will deploy and work with a PNNL wave Spotter buoy to measure local wave conditions and evaluate whether wave energy could power small on-site needs such as environmental sensors or dock lighting. They will analyze real-time wave data, compare observations to existing wave models, and assess what the local wave climate means for small wave energy converters. While data are being collected, students will also investigate how marine life interacts with in-water structures by observing fish behavior and biofouling development, gaining hands-on experience with snorkeling-based fieldwork and environmental monitoring.

In parallel, students will explore a bioinspired engineering challenge focused on wave energy converter orientation. Many devices must align with incoming waves to operate efficiently, often relying on restrictive mooring systems. Fish solve a similar problem through rheotaxis, using sensory feedback to orient and hold position in moving water. Students will study this biological strategy and explore how similar passive or low-energy mechanisms could inform the design of self-orienting wave energy converters, connecting biomechanics, fluid dynamics, and renewable energy engineering.

This project is ideal for engineering students interested in renewable energy, marine technology, or bioinspired design who want experience working with real ocean data and collaborating across disciplines. No prior marine biology experience is required—just curiosity and a willingness to work at the interface of engineering and the living ocean.

*This project is not listed on the NSF ETAP portal due to technical constraints: If you are interested in this project, please say so clearly in your writing prompts and we will be sure to list them as your first choice during the selection process!