Few invertebrates, terrestrial or marine, capture the human imagination as much as cephalopods, especially octopus. There’s something about those big eyes, those many arms, those remarkable behaviors…

Few invertebrates, terrestrial or marine, capture the human imagination as much as cephalopods, especially octopus. There’s something about those big eyes, those many arms, those remarkable behaviors…

In this essay, Willem connects the dots (the suckers?) between eyes, arms, behaviors — to explain how octopuses sense and process their world in unique ways.

Best,

Dr. Megan Dethier, FHL Director

Make a year-end gift

Smelling in the Dark with Eight Arms

by Willem Weertman

Most animals, including humans, rely heavily on vision to find food. But in the ocean — especially near the seafloor — vision is often unreliable. Deep water is dark, murky, and constantly moving. In these environments, chemical cues become a powerful source of information.

When a potential food item releases chemicals into moving water, those chemicals don’t spread evenly. Instead, they form long, patchy plumes shaped by turbulence — more like smoke from a candle than a smooth gradient. Many animals have evolved ways to follow these plumes upstream to their source, a behavior known as chemosensory plume-guided navigation. For decades, scientists have studied how animals like insects, crustaceans, and fish do this. Surprisingly, whether octopuses could do the same had never been clearly tested.

That gap in knowledge became the focus of my master’s research. I conducted the physical work for this study at the Friday Harbor Laboratories during the COVID lockdowns.

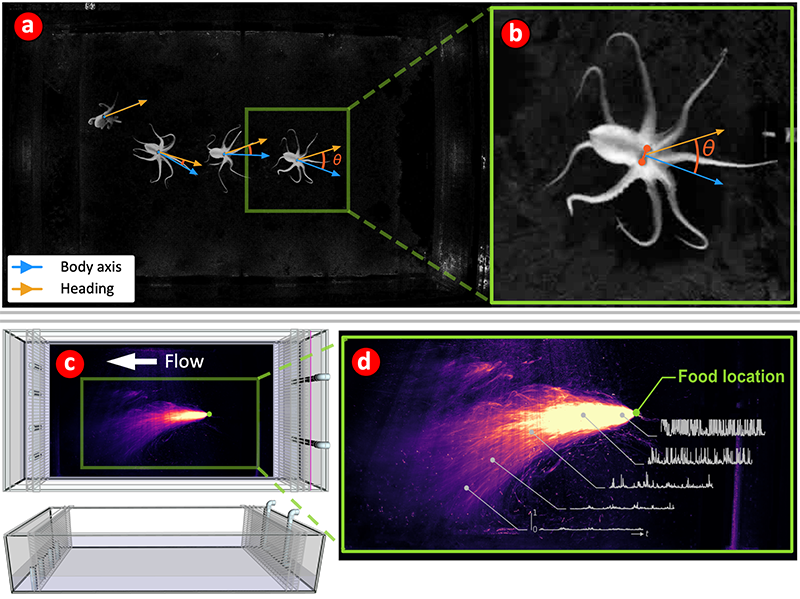

My interest in octopus behavior began earlier, during my undergraduate years, when I volunteered in the lab of David Gire at the University of Washington, working with Dominic Sivitilli on octopus arm control. David’s lab studies how mammals use smell to guide behavior, and that perspective shaped how I started thinking about octopuses — not just as visually clever animals, but as sensory specialists navigating complex environments (Figure 1).

When I looked into the literature on octopus chemosensation, I was surprised to find that although octopuses are known to “taste by touch” with their suckers and are capable water quality sensors, no one had shown whether they could use distant chemical plume cues to locate food. That question — Can octopuses track chemosensory plumes in flowing water? — became the foundation of my graduate work.

Understanding this question requires understanding what makes octopuses so unusual. Unlike most animals, octopuses do not have a centralized nervous system that tightly controls every movement. About two-thirds of their neurons are located in their arms, not their brain. As a result, the brain does not have a detailed map of where each arm is at every moment, nor does it receive continuous information about the precise position of each sucker.

This means that octopuses cannot control their arms the way we control our hands. Instead, the brain issues more general commands: search, reach, grasp; and the arms figure out the details locally. Each arm integrates information from touch, movement, and chemical cues on its own, coordinating with neighboring arms and only sending a compressed summary back to the brain.

Octopus suckers are especially important here. Each sucker is a multitasking sensor, capable of detecting touch, taste, and chemical signals at the same time. If octopuses were going to use chemosensory plumes to find food, the suckers were the most likely place where that information would be detected and acted upon.

To test this idea, I designed experiments that allowed octopuses to search for food in complete darkness, inside a flume of my design, using only chemical information carried by flowing seawater (Figure 2). I used two separate experiments: a three-discrimination task and a single station approach task. We found that octopuses consistently moved upstream toward food sources, choosing baited locations over un-baited ones far more often than chance would predict. When approaching food, they showed movement patterns characteristic of plume tracking seen in other animals: pausing, zig-zagging, and reorienting as if sampling the plume structure (Figure 3).

But what stood out most was how they moved.

Rather than re-orienting their bodies toward the food source, octopuses often made fast, decisive movements aligned with single arms. These “fast arm-aligned motions” occurred much more frequently when the octopus was actively tracking a food plume. This behavior suggests that individual arms and the suckers on them are making rapid, local decisions based on chemical cues, effectively leading the rest of the body (Figure 4).

In animals like rodents or insects, plume tracking is usually guided by paired sensory organs — two nostrils or two antennae — that compare signals across the body. Octopuses appear to be doing something very different. Instead of relying on a small number of centralized sensors, they distribute the task across eight arms and hundreds of suckers, each arm acting as a local decision-maker embedded directly in the motor system.

Why does this matter?

Octopuses are often described as intelligent because of their problem-solving abilities and behavioral flexibility. But intelligence is not just about cognition, it’s also about how bodies are built to process information. The octopus represents a fundamentally different solution to sensing and decision-making, one that is decentralized, embodied, and fast.

By showing that octopuses can track chemosensory plumes, and that they likely do so using their arms rather than a centralized “nose,” our work helps explain how these animals navigate dark, turbulent environments so effectively. More broadly, it offers insight into how nervous systems can be organized in radically different ways and still solve complex problems.

This research was conducted while I was a master’s student at Alaska Pacific University, with support from mentors including David Scheel and Dominic Sivitilli, and in close collaboration with David Gire at the University of Washington. All of the experimental work took place through FHL, with funding support from the Beatrice Crosby Booth Endowed Scholarship, Alan J. Kohn Endowed Fellowship, and crowdfunding from family and friends. Deep thanks to all the staff and researchers at the Friday Harbor Laboratories who made this project possible. I would especially like to acknowledge Joseph Ullmann, John Dorsett, Theresa Phillips, and Julia Kobelt for invaluable assistance.

Octopuses remind us that there is more than one way to sense the world and more than one way to be intelligent. Sometimes, understanding how an animal finds its dinner can change how we think about brains, bodies, and behavior altogether.

This research is described in detail at the reference below.

Reference:

Weertman W.L., Gopal V., Sivitilli D.M., Scheel D., and D.H. Gire. 2025. Octopus track chemosensory plumes to find food. PLoS One 20(10): e0330262. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0330262

Tide Bites is a monthly email with the latest news and stories about Friday Harbor Labs. Want more? Subscribe to Tide Bites or browse the archives.