Those of us steeped in traditions of western science – which involves hypothesis testing and is quantitative and unemotional – generally see eelgrass beds as great habitat and sites of high primary productivity, with hopefully an overlay of admiration for gleaming green beauty amid blue water. The essay below sees eelgrass through different eyes, in ways that long precede western science in the U.S. – ways that we can learn from. I am learning to appreciate the Coast Salish view of elements of the natural world: as our relatives, to be revered and cared for. The teamwork described here bridges these viewpoints, in ways that we hope will improve the health of the eelgrass beds as well as increase everyone’s understanding of our different cultures.

Those of us steeped in traditions of western science – which involves hypothesis testing and is quantitative and unemotional – generally see eelgrass beds as great habitat and sites of high primary productivity, with hopefully an overlay of admiration for gleaming green beauty amid blue water. The essay below sees eelgrass through different eyes, in ways that long precede western science in the U.S. – ways that we can learn from. I am learning to appreciate the Coast Salish view of elements of the natural world: as our relatives, to be revered and cared for. The teamwork described here bridges these viewpoints, in ways that we hope will improve the health of the eelgrass beds as well as increase everyone’s understanding of our different cultures.

Best,

Dr. Megan Dethier, FHL Director

Make your gift today

Local Chálem (Eelgrass) Restoration Starts a New Chapter With Ceremonial Blessing

by Richelle Tanner, with contributions from Sam Qol7ánten Barr & Sandy Wyllie-Echeverria

Dr. Richelle Tanner is an Assistant Professor and the Director of the Environmental Science & Policy Program at Chapman University in Southern California, where her research lab investigates the impacts of climate change on ecological and human communities. Her work focuses on the equitable and just distribution of environmental solutions in natural resource governance and the role of environmental uncertainty in ecosystem change. You can learn more at www.seacrlab.com and follow along on her adventures with students on TikTok @seacr_lab.

As we boarded a boat at the UW Friday Harbor Labs in late May, we all remarked how it was an unusually warm and sunny day compared to the characteristic Pacific Northwest gloom of the preceding week. We surmised it was “Good luck,” but was it more than that? A half hour later, we were rounding the mouth of Picnic Cove on Shaw Island, greeted by a glittering view of an expansive eelgrass meadow. Our research team unloaded two coolers of over 100 eelgrass plants, ready to be returned back to their home nearly 20 years after they arrived at FHL – first as a research project and later becoming the centerpiece of large display tanks that were an object of visitors’ admiration through outreach and courses. The Coast Salish Youth Coalition arrived at the Picnic Cove beach shortly after, led by children bursting out of vans to explore the water’s edge. As we all sat on the beach and discussed final project logistics, we watched a nun feed a bald eagle out of her hand – their nest was in a nearby tree overlooking the cove. It was shaping up to be a special day, indeed.

Our team came together through a shared commitment to returning eelgrass and their inhabitants to their ancestral home and supporting recovery efforts to this culturally and ecologically important ecosystem. Dr. Sandy Wyllie-Echeverria first connected me with this project when his grandson (5-year-old Nathan Rouleau) became infatuated with the sea hares living on the eelgrass, my research specialty. Over the last year, Sam Qol7ánten Barr from the Coast Salish Youth Coalition has taught us about the traditional importance of Chálem (the Samish/Lummi/Saanic term for eelgrass) and how this project could be executed. Our full team from UW, Chapman, and CSYC met in person for the first time during this historic eelgrass restoration on Shaw Island.

This latest Chálem restoration project in the San Juan Islands took place on this special day, to address a critical loss of intertidal eelgrass at Picnic Cove due to warming waters and other anthropogenic concerns, although the subtidal eelgrass is still thriving. The activities started with songs and drumming and culminated in a traditional preparation of the Chálem rhizome, a white and orange root section of the plant at the base of the leaves, for consumption. Zostera marina eelgrass is a protected species, making this culinary sampling an extremely rare and honored occasion, especially for long-time eelgrass researchers.

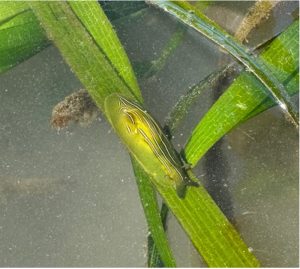

The plants destined for restoration were positioned in a grid pattern in the intertidal zone aligned with decades-old sampling locations maintained by UW FHL’s Sandy Wyllie-Echeverria. The planting effort sought to maximize potential success through a co-restoration of grazers taken directly from the FHL tanks, none more charismatic than the Phyllaplysia taylori “eelgrass sea hares.” As we continue to monitor the project’s progress, we hope to see a repopulation of the intertidal zone at Picnic Cove with not just eelgrass, but also its beneficial grazers like eelgrass sea hares for years to come.

Restoring the intertidal eelgrass at Picnic Cove has been a priority for local researchers and the Washington Department of Natural Resources, which holds the permitting for much of the Puget Sound’s eelgrass restoration activities. The team will continue to restore more eelgrass to the site throughout the summer and upcoming year thanks to funds from Seacology to the Coast Salish Youth Coalition and the Seagrass Conservation Project at FHL/UW. This site not only has ecological importance, but also the rich cultural and historical significance that exemplifies tribal use of the San Juan Islands.

Indigenous Connections to Eelgrass Meadows

Chálem has been used by the Northern Straits Coast Salish people as food, medicine, and in ceremonies since time immemorial. As a “first food”, Chálem is within one of the main sources of sustenance for Pacific Northwest tribes alongside salmon, berries, and roots like camas. These foods are considered relatives of the tribal peoples; companions to be visited in reciprocal relationship. Sam Qol7ánten Barr, executive director of the Coast Salish Youth Coalition, led tribal youth to visit with the eelgrass and sea hares in the extant eelgrass meadow at Picnic Cove as part of the restoration activities. One of the main goals of this project was to strengthen youth connections to first foods and build knowledge of the importance of Chálem in the livelihoods and cultures of the Northern Straits Coast Salish people.

Integrating Indigenous Knowledge into Modern Eelgrass Restoration and Monitoring

One of the hallmarks of Indigenous land stewardship is prioritizing relationships between species. When humans are involved, we think of this as reciprocity – when we take, we must tend. Indigenous land and resource management along the Pacific Northwest coast is the ultimate example of reciprocity for mutual success. Clam and tidal marsh root gardens, seasonal fish surveys, selective harvesting of herring roe and seabird eggs, and the careful thinning of eelgrass beds by twisting with a hemlock root are all practices that demonstrate the Coast Salish people’s skilled cultivation and ecological management skills. Nancy Turner, ethnobotanist, writes in a 2020 article summarizing a vast array of studies on traditional ecological knowledge in the coastal Pacific Northwest:

“[The cultivation methods] are interconnected and complex, reflecting ecological, technological, social, and spiritual practices that, together, have resulted in long-term productivity, greater abundance, and in some cases higher quality, of the resources, as well as their increased availability, diversity, and equitable distribution within communities.”

While modern eelgrass restoration methodology has not yet adopted these principles, some new practices draw inspiration from the prioritization of relationships between species. In this project, we undertook a co-restoration of eelgrass and their beneficial grazers, which remove a film of epiphytes from eelgrass leaves to increase photosynthetic efficiency. Phyllaplysia taylori, the eelgrass sea hare, is the most efficient grazer of epiphytes (Lewis and Boyer, 2014), earning a title in our educational programs as the “vacuum cleaner of the sea.” Our co-restoration considers seasonality in how we can best tend the relationship between eelgrass and sea hares, which is strongest when peak biomass occurs in early summer (both species are growing quickly and reproducing). Co-restoration projects are rare in the ocean and coastal habitats because of the necessary deep understanding of each species’ unique relationship with the environment and each other. To our knowledge, this is the first intentional co-restoration of this species pair – however, sea hares are known to hitch a ride on eelgrass restoration projects across the west coast every so often. As we continue the project, we are excited to monitor their reciprocal success in the restored plots throughout seasons and years.

This project highlights the importance of bridging Western and Indigenous principles in conservation and natural resource management, something that’s often referred to as a “nature-based solution.” However, we see it as one step further – returning to the naturalist point of view, where qualitative observations in the wild over generations hold the same weight as quantitative experiments and calculations in the lab. The replanting was also captured by video, which you can view on CSYC’s YouTube page here. How will restoration plans shift when we consider fostering relationships between plants, animals, and humans before tallying the acreage in a mitigation bank to maximize return on economic investment?

How Can We Get Involved?

We often get questions from residents, social media visitors, and even other researchers about how to be involved in this groundbreaking work. The first thing we recommend is doing some reading! Indigenous science is not yet commonplace in our state’s natural resource governance approach, but the more they hear from stakeholders about its importance, the easier it is to adopt into scientific practice and methodology development. These projects are also difficult to coordinate in terms of resources: even large-scale restoration projects done by consulting firms often rely on volunteer effort for success. Everyone has a unique skill or resource to contribute to a grassroots effort like ours, whether it’s helping to monitor plants, coordinate logistics, provide transportation, facilitate land access, or even fundraise. The most rewarding part of this project has been meeting the kind and generous folks who made this possible – we welcome any future friends as this restoration hopefully spans many, many more years.

References:

Cullis-Suzuki S., Wyllie-Echeverria S., Dick K.A., Sewid-Smith M.D., Recalma-Clutesi O.K., & N.J. Turner. 2015. Tending the meadows of the sea: A disturbance experiment based on traditional indigenous harvesting of Zostera marina L. (Zosteraceae) the southern region of Canada’s west coast. Aquatic Botany: 127, 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2015.07.001

Hughes B.B., Eby R., Van Dyke E., Tinker M.T., Marks C.I., Johnson K.S., & K. Wasson. 2013. Recovery of a top predator mediates negative eutrophic effects on seagrass. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: 110(38), 15313–15318.

Lewis J.T. & K.E. Boyer. 2014. Grazer Functional Roles, Induced Defenses, and Indirect Interactions: Implications for Eelgrass Restoration in San Francisco Bay. Diversity 14242818: 6(4), 751–770.

Joseph L. & N.J. Turner. 2020. “The old foods are the new foods!”: Erosion and revitalization of indigenous food systems in Northwestern North America. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems: 4, 596237.

Norris J.G., Wyllie-Echeverria S., Mumford T., Bailey A., & T. Turner. 1997. Estimating basal area coverage of subtidal seagrass beds using underwater videography. Aquatic Botany: 58(3–4), 269–287.

Shoemaker G., Wyllie-Echeverria S., & K. Britton-Simmons. 2007. 8 Variation in Zostera marina Morphology and Performance: Comparison of Intertidal and Subtidal Habitats at Three Sites in the San Juan Archipelago. Eelgrass Stressor-Response Project 2005-2007 Report: 101.

Tanner R. 2018. Predicting Phyllaplysia taylori (Anaspidea: Aplysiidae) presence in Northeastern Pacific estuaries to facilitate grazer community inclusion in eelgrass restoration. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science: 214, 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2018.09.011

Turner N.J. 2020. From “taking” to “tending”: Learning about Indigenous land and resource management on the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. ICES Journal of Marine Science: 77(7–8), 2472–2482. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsaa095

Wyllie-Echeverria S. & J. Ackerman. 2003. The Pacific Coast of North America. World Atlas of Seagrasses, Edited by Green, EP, Short, FT, 199–206. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Tide Bites is a monthly email with the latest news and stories about Friday Harbor Labs. Want more? Subscribe to Tide Bites or browse the archives.