Folks who first came to Friday Harbor as students, even decades ago, can likely relate to Taylor’s description of her first experience with the amazing diversity of the local marine flora and fauna intersecting with the deep knowledge of FHL instructors and the excitement of a cohort of students. We still hear from people who took a course back at FHL in the 1960s/70s about how it changed the trajectory of their life or helped them find a passion, even if this wasn’t necessarily marine science. We’d love to hear from more alums, from any era – we’ll be making a concerted effort to connect with alums over the next year to gather these stories. Taylor was fortunate (and persistent!) in finding ways to keep coming back in different roles, to our mutual benefit.

Best,

Dr. Megan Dethier, FHL Director

Make your gift today

Under the Sea(weed): A Journey From Student to Teacher and Researcher at FHL

by Taylor Hughes

Taylor is passionate about coastal ecology and resilience. As a master’s student at the University of Washington’s School of Marine and Environmental Affairs (SMEA), her research focuses on the ecology and physiology of bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) in response to changing environmental conditions in the Salish Sea. A 2024 Northwest Straits Foundation Caroline Gibson Scholar, she works to advance marine conservation through both research and outreach. Taylor expects to graduate in June 2025 and plans to work at the intersection of science and policy to support the resilience of Washington’s coastal communities.

The sun beat down on the deck of the R/V Centennial as a treasure trove from the sea was hoisted up and unceremoniously dumped onto the sorting table in front of me. A swarm of well-trained ZooBots (students from the UW Friday Harbor Labs [FHL] Zoology and Botany program) quickly descended upon the tangled mass and started sorting through the many kilos of rock, invertebrates, and algae. Veteran field biologists among the group greeted seaweeds that I had never seen by name, before tossing them back to the sea. By the end of the afternoon I was hooked on a field that I had never even heard of: phycology.

It was the spring of 2018 and I was among the lucky cohort of Cornell University students who got to venture out to FHL as part of an ocean research apprenticeship. Prior to this opportunity, I had an inkling that I was interested in seaweed but I hadn’t had a formal introduction to its biology or ecology, or methods of species identification. Fortunately, at FHL I found myself in one of the best locations in the world to study macroalgae and was invited to learn alongside the ZooBot students from Dr. Tom Mumford, one of the leading phycologists on the West Coast of North America. Returning to the lab after our ocean expedition, Tom showed us how to identify and save our algal finds for safekeeping, and despite my limited experience, I felt both eager and equipped to start studying seaweed as part of my burgeoning career in field biology.

The following summer, I participated in a kelp forest field ecology course at Hopkins Marine Station in Pacific Grove, CA, where I got acquainted with the diversity of marine life on the Monterey Peninsula and was trained as a scientific SCUBA diver. After a few years working professionally, I decided to pursue a master’s degree at UW specifically to study kelp, learn about marine policy, and conduct research at FHL.

The summer before starting my graduate studies, I had the opportunity to participate in the Marine Botany course at FHL, thanks in part to the generosity of the FHL Adopt-a-Student scholarship program. Once again, I found myself captivated by the numerous algae in the waters of San Juan Island and their strategies to survive, reproduce, and compete in the intertidal zone. I was of course grateful to soak up as much information as I could from the walking algal encyclopedia, Tom Mumford. Inspired by the work of FHL Postdoctoral Researcher Dr. Brooke Weigel, for my student research project I investigated whether elevated temperatures affect microscopic male and female kelp gametophytes differently. In addition to providing invaluable experience in experimental design and communicating research findings, this project allowed me to present later that Fall at my first academic conference, the Western Society of Naturalists.

My experience as a student at FHL has continued to shape my subsequent research and opportunities in graduate school. I am passionate about nearshore ecology and aspire to work at the science-policy interface to effectively integrate ecology into coastal zone management. In particular, I am interested in the recent declines of bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) in the Salish Sea. Bull kelp is an iconic species that provides essential habitat and resources to Washington’s nearshore ecosystems and was recently designated a State Marine Forest. Decadal-scale declines in populations throughout the Salish Sea are a cause for concern, and many scientists, managers, tribes, and community members have mobilized conservation, restoration, and research efforts to better understand the drivers and mechanisms of decline.

Through my Research Assistantship at SMEA, under the guidance of Dr. Terrie Klinger, I conducted informational interviews with many experts and practitioners in kelp forest ecology and conservation in the Salish Sea to inform the design of my thesis research and my time at SMEA. After being invited to join the Washington State Kelp Research and Monitoring Workgroup, I was introduced to Dr. Megan Dethier, Research Professor and Director of FHL. In one of those “right place, right time” moments, I was beginning graduate school in kelp forest ecology at the exact time that Megan was assembling a team of divers to conduct subtidal monitoring and research of bull kelp forests throughout the Salish Sea. The opportunity was almost too good to be true, and I was swiftly onboarded to the team.

In collaboration with researchers at the Washington State Department of Natural Resources, our project aims to monitor environmental conditions and community composition across a network of sites in the Salish Sea where bull kelp once thrived but now shows variable success. We are investigating how factors such as light, salinity, temperature, sedimentation, and biodiversity relate to the presence and extent of kelp forests. Our findings suggest that these patterns are highly site-specific — even differing at the basin level — highlighting the complexity of ecosystem dynamics and raising important questions about how best to conserve this iconic species. This opportunity has allowed me to collaborate with a team of all-female scientists, who spend most of their time underwater and all of their time thinking about kelp. As part of this team, I’ve had the chance to dive at sites across Washington State, analyze data at a regional scale, and help design field experiments to investigate potential drivers of kelp decline. One current project explores the hypothesis that other subtidal kelps may be shading juvenile bull kelp and limiting their recruitment success. This ongoing research is critical for informing kelp conservation strategies in the region.

In addition to fieldwork, I conducted a laboratory experiment for my master’s thesis investigating the microscopic life stages of bull kelp. Supported by an FHL Research Fellowship and a Phycological Society of America Grant-in-Aid of Research, I tested how elevated seawater temperatures affect the density of female and male gametophytes and the production of juvenile sporophytes. This work built on a pilot study I conducted at FHL the previous summer. I found that the density of female gametophytes declined with increasing temperature, while the density of male gametophytes remained unaffected — revealing sex-specific thermal sensitivities. These differences led to shifts in population demographics and reduced reproductive success. My findings indicate that microscopic bull kelp stages are vulnerable to temperature increases already occurring in parts of the Salish Sea during summer months. As a result, this research supports prioritizing conservation and restoration in cooler, more thermally-stable environments that may better support long-term bull kelp persistence.

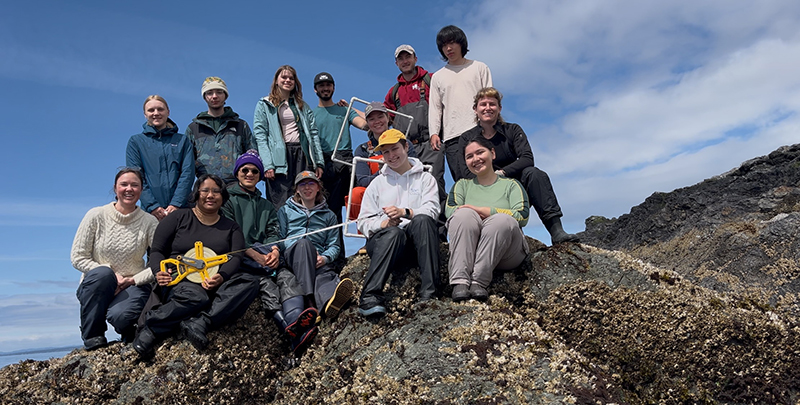

Part of what makes FHL such a “sticky” place, as some say, is the lasting sense of community here. Studying and researching here got me hooked, and the opportunity to be a Teaching Assistant (T.A.) at FHL has allowed me to stay connected while finishing my graduate program. During my time in graduate school, I have served as a T.A. for the Marine Conservation Ecology and Marine Botany courses. Through these experiences, I had the chance to help undergraduate and graduate students find their sea(weed) legs in the intertidal and design amazing projects about intertidal ecology and organismal biology. Living for five to ten week stretches at FHL has also allowed me to connect with the staff, researchers, and residents who make this place feel like a home for marine scientists at any stage of their careers.

As this period at FHL draws to a close, I cannot help but reflect on all the connections I have made and ways I have grown since I first showed up in Friday Harbor eight years ago. From my first foray as an honorary ZooBot to becoming part of the ZooBot teaching team, FHL has provided countless opportunities to learn and develop as a student, teacher, researcher, and marine steward. While some things have changed, as I ride out on the R/V Kittiwake for an algae dredge with my students, I am reminded that one thing you can always count on at FHL is that there will be students equipped with notebooks, buckets, boundless curiosity, and endless questions.

Tide Bites is a monthly email with the latest news and stories about Friday Harbor Labs. Want more? Subscribe to Tide Bites or browse the archives.