One of the challenges for researchers doing field work on San Juan Island is the limited numbers of sites with public shoreline access – and of course the corollary that any place with public access will have a lot of public traffic, making it very hard to do undisturbed observations and experiments. FHL has a few “fairy godparents” who alleviate this challenge by providing limited access to their private shorelines. Over the years this wonderful group has included the MacGinities, Susan Swindells, Laurie Kalbach, the Hunts, and others – and for several researchers (including myself) – the Ragen family. We love not only this access to special sites, but the opportunity to connect to community members about the science going on at FHL.

One of the challenges for researchers doing field work on San Juan Island is the limited numbers of sites with public shoreline access – and of course the corollary that any place with public access will have a lot of public traffic, making it very hard to do undisturbed observations and experiments. FHL has a few “fairy godparents” who alleviate this challenge by providing limited access to their private shorelines. Over the years this wonderful group has included the MacGinities, Susan Swindells, Laurie Kalbach, the Hunts, and others – and for several researchers (including myself) – the Ragen family. We love not only this access to special sites, but the opportunity to connect to community members about the science going on at FHL.

If you would like to contribute to this great cause and help foster the next generation of marine scientists, you can make a gift here.

The FHL Effect: One Researcher’s Journey from Whales to (Sea)weed

by Kaitlyn Tonra

I arrived at Friday Harbor Labs for the first time in the summer of 2018. I had just finished my second year at Oberlin College and was thrilled to swap a small town in Ohio for an island in Washington for a few months. At the end of my first day on campus, I sat on the porch of my hut and watched the ferries glide in and out of the harbor as the lights began to glow in the windows of the little lab buildings at the bottom of the hill. I was convinced that this was the moment that something life-changing was beginning, so I did my best to memorize every detail.

I had the right idea, but despite my best efforts the actual moment went completely unnoticed a few days later, on a windy afternoon field trip to Cattle Point. It was our first Marine Botany field trip and Dr. Thomas Mumford, affectionately called Tom by his students, was pointing out areas of the intertidal zone and different species of algae present in each. The high intertidal only has a few species that can withstand stressful conditions, and closer to the water the diversity of species increases with vibrant combinations of red, green, and golden-brown algae competing for space. We were nearing the waterline when Tom stopped to point out a squat, wrinkly species called Hedophyllum sessile.

Hedophyllum, or sea cabbage, is a common kelp found in the intertidal zones of Washington and Oregon. Tom explained that a recent study by an Oregon State University graduate student had found that the success of Hedophyllum is strongly related to the presence of coralline algae, a group of red seaweeds with calcified cell walls that allow them to create rigid structures. This topic seemed interesting enough for a class project, and I figured it would at least help pass the time until I could do what I really came to FHL for: whale watching in a Marine Birds and Mammals course. I spent the next few weeks working with Tom, my lab partner Emily, and Dr. Wilson Freshwater to look for evidence of microscopic kelp gametophytes (the “seed” stage of the kelp life cycle) in the tissues of coralline algae. Corallines are not palatable to many species of herbivores, so we wanted to know if they could be promoting kelp growth by providing a refuge from grazers for the gametophyte stage. My interest in this research question grew over the course of the summer. By the time my next course started, I found my binoculars wandering towards kelp beds instead of the seals I was supposed to be counting. I went on to present my Marine Botany project at a Western Society of Naturalists conference that Fall, and in 2020, I was awarded a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to expand the project as part of a PhD dissertation.

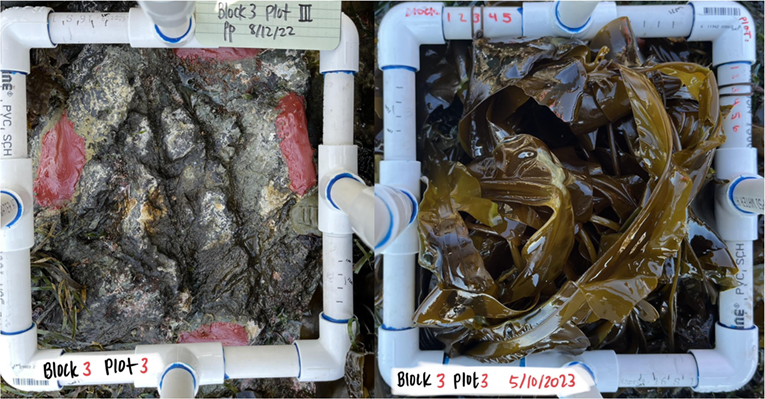

I joined the Lubchenco-Menge Lab at Oregon State University in the Fall of 2020. After a brief foray into coral reef ecology, I returned to FHL in 2022 to start a long-term field experiment on the southwest edge of San Juan Island, at a secluded site called Pile Point. I wanted to better understand the mechanism behind the positive association between corallines and Hedophyllum. I was especially interested in two aspects of this relationship: the effect of grazing by the chiton Katharina tunicata on Hedophyllum recruitment (success of young individuals), and the role of gametophyte “seed banks” which aid in the re-establishment of a population after the kelp are removed. To evaluate these factors and their interactive effects, I removed adult Hedophyllum from plots with corallines, plots without corallines, and plots that were sterilized to remove gametophytes. I then studied the effect of grazers on the recovery process in each, by revisiting my experiment roughly every month for one year to record new kelp growth, document the community recovery process by photographing the plots, and take DNA swabs to monitor the presence of gametophytes.

I can easily count how many adults of each species are present in each plot, and the DNA swabs offer a way for me to keep track of which species are present in the microscopic gametophyte community as well. I loved getting to visit FHL so often, but I reduced my sampling frequency to something more manageable after making the 20-hour roundtrip between Corvallis and Friday Harbor 10 times in one year.

This project is a major part of my PhD, but just a small contribution to the legacy of ecological research at Pile Point; it’s a uniquely diverse and incredibly beautiful place to work that contains some of the most extensive Hedophyllum beds on the entire island. This ecosystem has flourished under the care and stewardship of the Ragen Family, who have owned the property and supported FHL research for decades. Their generosity has made my research possible, and I am grateful for the opportunity to carry out my experiment at the site where so much pioneering work on Hedophyllum and Katharina has been done by researchers like Drs. Megan Dethier, David Duggins, and Jennifer Burnaford.

Almost four years after my fateful trip to Cattle Point, I stood in the same spot where I had first learned about Hedophyllum and explained its ecology to my own students in the spring ZooBot class. It’s amazing to think that a brief summer visit to FHL wound up shaping my career and life so profoundly, but I know that my story is far from unique. The “FHL Effect” that draws people back to the Labs is a product of its people and sense of community.

There isn’t space in a single Tide Bite to thank everyone that has supported me over the past few years, but I wouldn’t be where I am today without mentorship from Drs. Megan Dethier, Tom Mumford, and Wilson Freshwater, and financial support from Yvonne Powell via the Adopt-a-Student scholarship, the FHL Student Fellowship fund, and Richard and Megumi Strathmann Endowed Fellowship. My current projects are made possible by the Brooks and Suzanne Ragen Friday Harbor Laboratories Endowed Scholarship. Susie and her family have been welcoming, kind, and interested in my research every time that I visit Pile Point, and I am excited to be going back there this summer to continue my experiment.

Tide Bites is a monthly email with the latest news and stories about Friday Harbor Labs. Want more? Subscribe to Tide Bites or browse the archives.