This essay is a departure from our usual marine-organism stories – but it starts with sea slugs, and transitions to a topic of special interest to women in science and parents of young children. I particularly appreciate seeing scientific data that bears on such a controversial issue, counteracting the abundant fake news in the popular press! And it is extra-special that much of the work done in producing Lise’s books happened at FHL’s Whiteley Center. Lise agrees with all scholars who come to work at the Center that it is a setting that encourages enormous creativity and productivity. Readers who are interested in experiencing this phrontistery (google the term!) should check out our website.

This essay is a departure from our usual marine-organism stories – but it starts with sea slugs, and transitions to a topic of special interest to women in science and parents of young children. I particularly appreciate seeing scientific data that bears on such a controversial issue, counteracting the abundant fake news in the popular press! And it is extra-special that much of the work done in producing Lise’s books happened at FHL’s Whiteley Center. Lise agrees with all scholars who come to work at the Center that it is a setting that encourages enormous creativity and productivity. Readers who are interested in experiencing this phrontistery (google the term!) should check out our website.

Gender and Science at FHL

by Lise Eliot, PhD

Professor of Neuroscience and member of the Stanson Toshok Center for Brain Function and Repair at the Chicago Medical School of Rosalind Franklin University in North Chicago, IL.

I am not a marine biologist, despite completing a PhD dissertation on the sea slug Aplysia californica. Nonetheless, FHL has played a big part in my career, thanks to many summers when it offered me the serenity and space to pursue new projects in my actual field: neuroscience. My first stay was in the summer of 1994 with my husband Bill Frost and our 3-month-old daughter, Julia. Bill had been coming to FHL since 1986, which you can read about in recent Tide Bite. I was on the East coast for most of this time, including several lucky stints at the Marine Biology Lab in Woods Hole. But once Julia came along, we prioritized family togetherness and began the first of many blissful, productive summers at FHL.

Along with other marine mollusks, Aplysia is a superb model for studying the neural basis of behavior. My graduate work with Eric Kandel at Columbia University focused on the cellular mechanisms underlying synaptic plasticity — that is, the changes in strength of neural connections that underlie learning, memory and behavioral development. For my post-doc, I followed the fashion and switched to studying similar questions in rodent brains. But for a variety of reasons, my interest in cellular neurophysiology started to wane, as other topics rose to the fore for my scholarly pursuit. I had an outstanding post-doc advisor, Dan Johnston at Baylor College of Medicine. But Dan’s large lab was all male at that time, except for myself and his secretary. This was not a great arrangement when your interests are already drifting and you are trying to keep up with a bunch of biophysics jocks. Not to mention the Sports Illustrated posters of bikini-clad women I had to encounter above a couple of their electrophysiology rigs. Did I lose interest in cellular neuroscience, or did that science lose interest in me?

Gender is always an issue in science … for women. After Julia was born I had to stare down my priorities, and realized that identifying the specific calcium channel responsible for neurotransmitter release in the rat hippocampus was not one of them. But fortunately, I found a new niche where my broader interest in neuroplasticity could be put to good use. That first summer at FHL with Bill and Julia gave me a chance to breathe (yes, she was a very easy baby!) and to realize that my real interest in neuroscience lies at the bigger-picture level. During my pregnancy, I’d been frustrated by not being able to find a good book on babies’ brain development. And now that we had a real live baby in our arms, I couldn’t stop thinking, “What’s going on inside little Julia’s head?” So later that year I quit my post-doc and managed to sell the proposal for my first book, What’s Going On In There? How the Brain and Mind Develop in the First Five Years of Life, to Bantam Books. It took me four years to write, including more memorable summers in the FHL library. But this “odyssey of discovery” (as we billed it on the book jacket) was worth the effort. I now had two children, a deep knowledge of human brain development, and a new direction for my scientific career.

Did I mention that child #2 was a boy? Sammy was born in 1996, followed by Toby in 1999, and it wasn’t long before I started wondering about gender differences in their brains. This is always a hot topic, but at the time there was a surge of parenting books and articles about supposed “hard-wired” differences between boys and girls. As a scientist whose research had always focused on neuroplasticity, I knew this was deeply misguided. I soon decided what my second book would be about, and also discovered the newly-built Whiteley Center at FHL as a perfect place to begin work on it.

I wrote the proposal and much of the manuscript for Pink Brain, Blue Brain: How Small Differences Grow Into Troublesome Gaps – And What We Can Do About It, at FHL and the beautiful Whiteley Center. Published in 2009, the book explains when and how gender differences emerge during child and adolescent development. Far from being “hard-wired,” the data show that gender differences grow as children do: through intimate interaction with the world around them, including parents, peers, toys, clothes, and a thoroughly divided culture where everything we say or do has an implicit gender label attached to it.

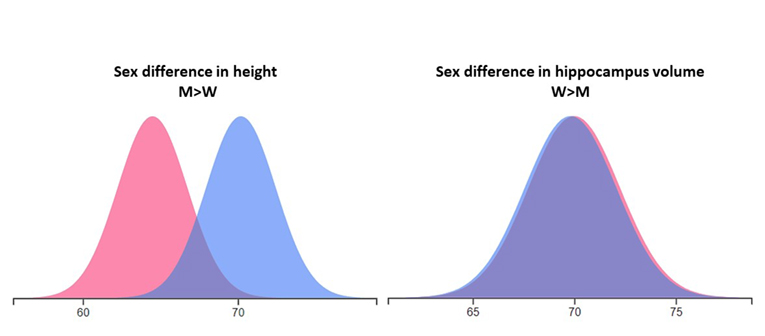

The one thing that is NOT clearly different between boys and girls is the brain itself. Although I started my research, like any biologist, assuming that the human brain undergoes some kind of sexual differentiation in early development, a thorough analysis of the literature caused me to eventually abandon this idea. In 2021, I published a major review titled, “Dump the Dimorphism” to emphasize the trivial size and unreliable nature of sex differences that have been found after some 30 years of human brain imaging research.

Among the topics I’ve addressed in my book and articles are gender gaps in STEM careers. If men are more prevalent in science, technology, engineering, and other math-intensive fields such as finance, it is hardly a matter of their brains being uniquely evolved for such pursuits. The gaps in K-12 math achievement have disappeared over the past few decades, and girls are now taking as many AP science courses as boys. But what still differs are those implicit labels and assumptions about who is “brilliant” or “pioneering” or a “leader” – beliefs that stick harder the higher you go in the scientific hierarchy.

Unless you happen to be at Friday Harbor Labs! Compared to my early days, the gender shift among marine biologists has been seismic. Oh, there were plenty of women scientists at FHL in the 1990s, but you had to go up to the Bunny Lawn to find many of them. They were there watching the kids, while their husbands were more often the ones in the labs doing experiments.

It’s been wonderful to see this shift over the decades, to what looks now to be a much better gender balance among lab heads and a striking predominance of women among the FHL student body. Like every career, marine biology has an implicit gender label which I have witnessed flip over my professional life. Neuroscience has taken a similar trajectory, with more women than men now entering the field.

Who would have thought, 30 years ago, that we would need to work harder to attract young men to these fields? But that’s how it goes when gender differences are a product of our society, not our brains.

References

Eliot L. 2021. Brain Development and physical aggression: How a small gender difference grows into a violence problem. Current Anthropology: 62 (Suppl. 23), 66-78.

Eliot L. 2019. Neurosexism: The myth that men and women have different brains. Nature: 566, 453-54.

Eliot L. 2017. The dearth of women in tech is nothing to do with testosterone. New Scientist: Issue 3147.

Eliot L. 2011. The trouble with sex differences. Neuron: 72, 895-98.

Eliot L. 2009. Pink Brain, Blue Brain: How Small Differences Grow into Troublesome Gaps – And What We Can Do About It. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin-Harcourt.

Eliot L. 1999. What’s Going On in There? How the Brain and Mind Develop in the First Five Years of Life. New York: Bantam.

Eliot L., Beery A.K., Jacobs E.G., LeBlanc H.F., Maney D.L., and M.M. McCarthy. 2023. Why and how to account for sex and gender in brain and behavioral research. Journal of Neuroscience: 43(37), 6344-6356.

Eliot L., Ahmed A., Khan H., and J. Patel. 2021. Dump the “dimorphism”: Comprehensive synthesis of human brain studies reveals few male-female differences beyond size. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews: 125, 667-97.

Rauch J.M. and L. Eliot. 2022. Breaking the binary: Gender versus sex analysis in human brain imaging. NeuroImage: 119732.

Rippon G., Eliot L., Genon S., and D. Joel. 2021. How hype and hyperbole distort the neuroscience of sex differences. PLoS Biology: 19(5), e3001253.